Long before the industrial refinement of sweeteners, sugar cane and fruit served as the primary sources of sweetness across ancient civilisations. Early Mesopotamians extracted sugary sap from dates; Indians crystalised sugar cane juice over 2,000 years ago; and indigenous cultures chewed raw honeycomb or maple tree bark for their natural sugars. These sources – fruits, honey, sugar cane – contain the foundational sweet compounds we now separate, package, and analyse extensively: fructose, glucose, and sucrose.

In the modern food system, these sugars show up everywhere – from the obvious (table sugar, sodas, fruit juices) to the less recognisable (in salad dressings, bread, cheese). Chemically categorised as carbohydrates, all three serve as energy substrates, though they differ significantly in structure, absorption, and metabolic effects. The food industry uses each strategically: fructose for its intense sweetness, glucose for its rapid energy contribution, and sucrose for its stability and versatility as a compound molecule.

As carbohydrates, their primary function in the human diet is clear: they supply energy. Yet despite sharing that role, they do not behave identically once consumed. Curious why confectionery contains glucose, your morning fruit smoothie is high in fructose and why a sports drink contains a ratio of both? Or why sucrose is the default for baking? The answers begin with understanding the chemistry behind these carbohydrates – and end with reconsidering how they influence appetite, metabolism, and energy use.

How do Fructose, Glucose, and Sucrose Differ at the Molecular Level?

Understanding the structural, metabolic, and functional distinctions between the primary dietary saccharides – glucose, fructose, and sucrose – is fundamental to advanced nutritional science and food formulation. These carbohydrates, though all classified as simple sugars, exhibit distinct molecular configurations, glycosidic linkages, and metabolic rates.

- Glucose and fructose are both hexose monosaccharides but differ in functional groups (aldehyde vs. ketone), influencing their reactivity, sweetness intensity, and enzymatic utilization.

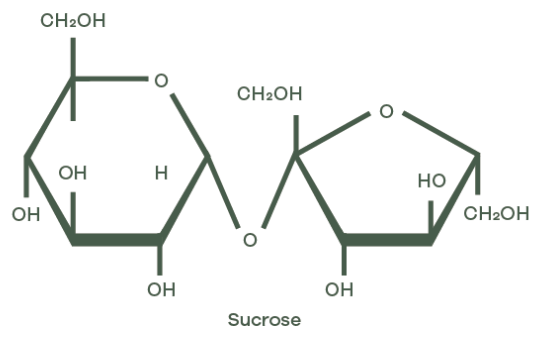

- Sucrose, a disaccharide composed of glucose and fructose via an α(1→2)β glycosidic bond, demonstrates unique hydrolytic and physicochemical properties.

Molecular Composition of Fructose, Glucose, and Sucrose

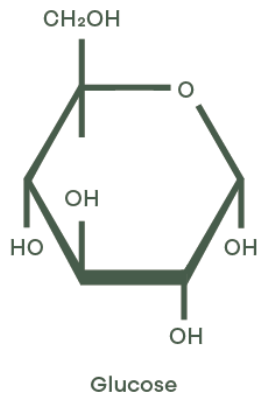

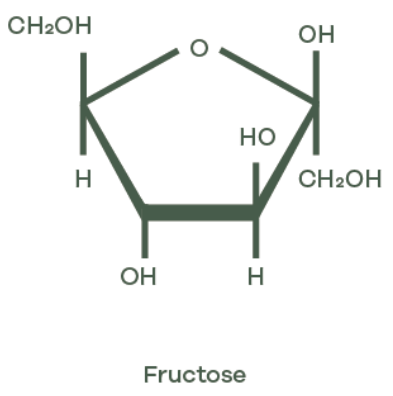

Fructose and glucose share the same molecular formula (C6H12O6) yet their molecular architecture sets them apart. Both are monosaccharides, the most basic units of carbohydrates. Sucrose, on the other hand, is a disaccharide, meaning it’s made by chemically bonding two monosaccharides together.

Here’s the breakdown:

- Glucose is classified as an aldohexose, featuring an aldehyde group at the first carbon position.

- Fructose belongs to the ketohexose family, incorporating a ketone group at the second carbon.

- Sucrose consists of one glucose and one fructose molecule, joined through a glycosidic linkage between the C1 of glucose and the C2 of fructose.

Structural Variances and Why They Matter

The difference in functional groups – aldehyde in glucose versus ketone in fructose – directly affects molecular behaviour. For example, in aqueous solutions, glucose tends to form a six-membered ring structure known as a pyranose, while fructose more commonly takes on a five-membered ring form called a furanose. These cyclic structures dominate at physiological pH – around 7.4 – and influence how each sugar interacts with enzymes during metabolism.

Calories per gram don’t change, but biochemical reactivity does. The ring size and functional group location impact enzymatic recognition, solubility, and even how each sugar participates in non-enzymatic glycation reactions. Fructose, with its five-membered ring and higher chemical reactivity, undergoes Maillard reactions more rapidly than glucose under the same heat conditions.

The Formation of Sucrose from Fructose and Glucose

When glucose and fructose link up to form sucrose, a dehydration synthesis reaction kicks in. One water molecule is eliminated as the hydroxyl group of glucose’s C1 and the hydrogen of fructose’s C2 come together. This stable glycosidic linkage (an α(1→2) bond) blocks the carbonyl groups of both monosaccharides, removing their ability to act as reducing sugars. In simpler terms, the bond between glucose and fructose hides their reactive parts, so sucrose doesn’t behave like a typical sugar when heated or processed.

Why does that matter? Because the locked-out carbonyl groups mean sucrose doesn’t participate in reducing reactions like glucose and fructose do. That changes how it behaves in food chemistry, especially when exposed to heat during caramelisation or baking processes. Sucrose remains chemically inactive until it’s cleaved, either by an enzyme like sucrase in the body, or by a combination of heat, moisture, or acid during cooking, which breaks it down into its component monosaccharides for absorption or further reaction.

It’s worth noting that despite their differences in behaviour and structure, glucose, fructose, and sucrose, are classified as sugars. On food labels, they’re often grouped under the general term “sugars”, reflecting their similar role as sweet-tasting carbohydrates and their metabolic contribution to energy intake.

Sweetness Levels and Taste Perception: Fructose, Glucose, and Sucrose

Sweetness is not uniform across sugars. Fructose, glucose, and sucrose differ significantly in how sweet they taste, bite for bite. On a standard sweetness scale where sucrose is assigned a reference value of 1.0, fructose scores higher:

- Fructose: 1.2 to 1.8, depending on concentration and temperature

- Sucrose: 1.0 (baseline)

- Glucose: 0.6 to 0.7

Fructose can taste up to 80% sweeter than sucrose and more than twice as sweet as glucose under certain conditions. Temperature plays a role – fructose’s sweetness becomes more pronounced at lower temperatures, making it a go-to choice in cold beverages and frozen desserts.

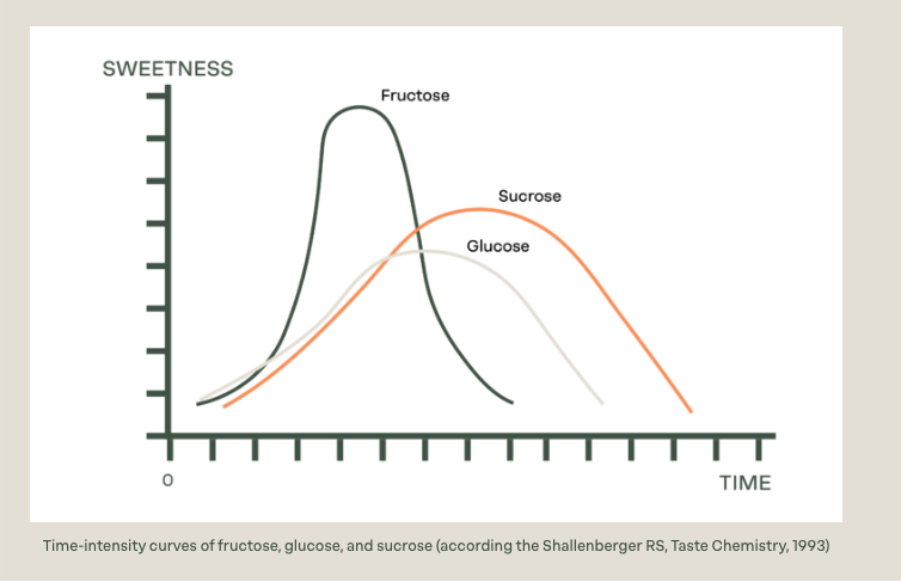

Sweetness isn’t just about intensity; the time–intensity curve matters too. This curve describes how sweetness develops, peaks, and fades over time in the mouth. For example:

- Sucrose has a well-balanced time–intensity profile with a quick onset, moderate peak, and clean finish, which is why it’s so widely used.

- Fructose typically shows a rapid onset and prolonged lingering sweetness, especially noticeable at cooler temperatures.

- Glucose tends to have a milder sweetness with a faster decay, meaning it doesn’t linger on the palate.

Understanding these curves is essential in product development, especially when blending sweeteners or targeting specific sensory profiles in applications like beverages, dairy, or confectionery.

Impact on the Sensory Experience in Beverages and Food

Sweetness perception varies by individual. Even when tasting chemically pure fructose, people may perceive different intensities. This subjectivity means sweetness scales serve only as a general guide.

The sensory role of sugar goes beyond taste; it also influences mouthfeel, enhances or mutes other flavours, and even affects aroma through synergistic interactions. Fructose, naturally present in fruits, tends to boost fruitiness. Sucrose enhances chocolate and vanilla notes. Glucose, by contrast, may slightly flatten complex flavour profiles.

Fructose delivers a more intense, rapidly perceived sweetness, often described as smoother and more pronounced in cold or liquid applications.

Sucrose offers balance. Its clean, steady onset and even dissipation create a familiar sweetness curve, ideal for a wide range of products from candies and baked goods to standard soft drinks.

Glucose has a milder, flatter sweetness profile. While less intense, it works well in formulations like energy gels and sports drinks where quick energy release is prioritised over flavour impact.

Ultimately, sugar preference is shaped by cultural norms, emotional cues, and product context. Would a sharp apple cider benefit from fructose’s punch? Would a caramel latte lose its creamy roundness with glucose? These are the real-world formulation choices food and beverage developers make every day.

How Fructose, Glucose, and Sucrose Differ in Glycaemic Index and Blood Sugar Response

The glycaemic index (GI) provides a numerical scale – ranging from 0 to 100 – that ranks carbohydrates based on how quickly they raise blood glucose levels after consumption. Each sugar behaves differently in this regard.

- Glucose has a GI of 100 – by definition, it sets the benchmark for the scale.

- Fructose scores much lower, with a GI around 15 to 25 depending on the test method and food matrix.

- Sucrose falls in between, usually around 65, since it’s a disaccharide composed of glucose and fructose in a 1:1 ratio.

These values reflect how rapidly each sugar is digested and absorbed. Because glucose enters the bloodstream directly, it causes a sharp increase in blood sugar. Fructose, by contrast, is primarily metabolised in the liver before it can influence blood glucose levels, which tempers its immediate impact.

Differences in Blood Glucose and Insulin Response

The glycaemic index only tells part of the story. Equally important is how each sugar affects insulin secretion. Glucose triggers a strong insulin response. Once absorbed, it signals the pancreas to release insulin to help cells uptake the sugar for energy or storage. Fructose is not a direct trigger for insulin response. This is due to the low levels of the fructose transporter GLUT5 in the pancreatic beta cells.

Sucrose, containing both glucose and fructose, yields a mixed effect: insulin levels rise, but not as rapidly or as high as with pure glucose. A 2002 clinical study published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition demonstrated that fructose consumption results in considerably lower postprandial (after eating) insulin and glucose levels compared to the same calorific amount of glucose.

This divergence in glycaemic and insulin responses has prompted extensive research into how carbohydrate composition affects metabolic health, particularly concerning insulin sensitivity, type 2 diabetes risk, and dietary glycaemic load.

Implications for Beverage Manufacturers

The GI and insulin response of different sugars directly influence formulation strategies in the beverage sector. Drinks made primarily with glucose-based sweeteners, such as dextrose (D-Glucose), rank high on the glycaemic index, rapidly impacting blood sugar. Sucrose-sweetened beverages come next, while those formulated with high-fructose ingredients generally elicit a lower glycaemic response.

This makes fructose-containing sweeteners appealing for products targeting low-GI or sustained energy claims. However, manufacturers must balance this advantage with broader health concerns tied to fructose metabolism, especially in high concentrations.

Lower-GI profiles can also be used as selling points for sports drinks, meal replacements, and functional beverages. By adjusting the ratio of sugars and incorporating slower-digesting carbohydrates or fibre, brands can fine-tune glycaemic impact without sacrificing sweetness.

How the Body Handles Fructose, Glucose, and Sucrose: Metabolism and Health Impacts

Distinct Metabolic Pathways for Each Sugar

While fructose, glucose, and sucrose are all simple sugars, the body processes each through distinct metabolic routes. Glucose enters the bloodstream directly and triggers insulin release. Cells throughout the body absorb and utilise it immediately for energy or store it as glycogen in the liver and muscles.

Fructose behaves differently. It bypasses the insulin pathway and is primarily metabolised in the liver, though small amounts can also be processed in tissues like skeletal muscle and kidneys. Upon arrival in the liver, fructose is converted into intermediates like glyceraldehyde and dihydroxyacetone phosphate. These intermediates can be used to synthesise triglycerides, which contributes to increased fat accumulation when intake is excessive.

Sucrose, commonly seen in the form of table sugar, is a disaccharide made of one molecule of glucose and one of fructose. During digestion, the enzyme sucrase breaks it down in the small intestine, releasing the individual monosaccharides, which are then metabolised along the pathways already described.

Excess Sugar and Chronic Diseases: What the Data Shows

- Excess glucose raises blood insulin chronically, increasing fat storage and risk of insulin resistance.

- Fructose, primarily metabolised in the liver, contributes disproportionately to de novo lipogenesis – the creation of fat from non-fat substrates.

- Sucrose supplies both glucose and fructose, magnifying metabolic strain when consumed in large quantities.

Setting Intake Boundaries

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends keeping free sugar intake below 10% of total daily energy intake. Translating this into numbers: for a 2,000 kcal/day diet, that’s about 50 grams of added sugars, or roughly 12 teaspoons per day.

The American Heart Association (AHA) suggests even lower thresholds: no more than 36 grams (9 teaspoons) per day for men and 25 grams (6 teaspoons) for women, given the strong association between excess sugar and cardiovascular risk.

Despite metabolic differences, the common denominator across all three sugars is quantity. The body handles moderate amounts effectively, but chronic overconsumption, especially through sugary beverages and processed foods, overwhelms metabolic systems and leads to long-term health damage.

Please note: The information provided above is for reference and informational purposes only. Ingredient use and health-related claims should always be evaluated in the context of local regulatory frameworks. We recommend consulting the relevant authorities or regulatory experts to ensure compliance within your specific market.

Conclusion

The differences between fructose, glucose, and sucrose are far more than just their taste profiles. Each sugar has unique chemical structures, metabolic pathways, and distinct effects on the body, influencing their applications in the food and beverage industry. Fructose, with its high sweetness and low glycaemic impact, is commonly used in beverages and desserts, while glucose provides quick energy, making it ideal for sports products. Sucrose, as a stable and versatile compound, remains the standard for baking and general-purpose sweetening.

However, their effects on health are important to consider, particularly considering the growing concerns over excess sugar consumption. High intake of fructose, especially from high-fructose corn syrup, has been linked to various metabolic disorders, highlighting the need for moderation. Food manufacturers must also factor in the functional benefits of each sugar, such as moisture retention, browning, and texture enhancement, when formulating products. By understanding the distinct properties and health implications of fructose, glucose, and sucrose, companies can make more informed decisions to meet both consumer preferences and health-conscious trends.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Not inherently. All three serve as energy sources and are metabolised differently. Problems arise with overconsumption, particularly in the form of added sugars in processed foods. Moderation and context — such as total diet and activity level — are key.

Fructose is primarily metabolised in the liver, where excess intake can promote fat production and contribute to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Unlike glucose, it doesn’t trigger insulin release or suppress appetite effectively, which can lead to overeating.

Sucrose is a disaccharide made of bonded glucose and fructose (1:1 ratio), while HFCS is a blend of free glucose and fructose, typically around 55% fructose and 42% glucose. HFCS is a liquid and easier to integrate into formulations, but functionally similar to sucrose in sweetness and metabolism.

Yes. While the chemical structure is the same, sugars in whole fruits come with fibre, water, and micronutrients that slow digestion and reduce blood sugar spikes. Added sugars lack these buffering components and are absorbed more rapidly.

Glucose has the highest GI at 100, making it the fastest to raise blood sugar. Sucrose is moderate (around 65), and fructose is much lower (15–25), though its low GI doesn’t necessarily mean it’s healthier in excess.

Fructose is the sweetest simple sugar, especially at cooler temperatures. It can be up to 80% sweeter than sucrose, allowing for smaller quantities to be used in formulations without sacrificing perceived sweetness.

Glucose offers immediate energy and a rapid glycaemic response, making it ideal for products aimed at quick recovery or energy replenishment, such as sports drinks or gels.

Yes. Sucrose remains the benchmark for sweetness and is preferred in many markets for its clean flavour and consumer acceptance. In some countries, HFCS is less accepted due to public perception.

It’s possible, but unnecessary for most. Naturally occurring sugars in fruits and dairy are part of a balanced diet. The focus should be on reducing added sugars and understanding where they appear in processed foods.

Not just taste. These sugars affect texture, shelf life, moisture retention, browning, and even how flavours develop. Their roles are functional as well as sensory.

How can we help?

At Lehmann Ingredients, our 35 years of experiences in sourcing and supplying top-tier ingredients makes us a trusted partner for businesses of all sizes, both in the UK and internationally. Our expertise in sweeteners and more specifically, carbohydrates has helped industry leaders and startups alike bring quality and innovation to their products. If you’re looking to enhance your formulations with reliable, high-quality sweeteners, our team is here to help. Reach out to us at enquiries@lehmanningredients.co.uk or call +44 (0)1524 581 560 to explore our full portfolio and discover how we can support your ingredient needs.