Why E Numbers Cause Confusion

Few elements of a food label generate as much uncertainty as E numbers. For many shoppers, they have become shorthand for “ultra-processed” or “chemical” foods; something unfamiliar, technical, and therefore assumed to be undesirable. This perception has been reinforced by headlines, social media, and the broader conversation around food processing, where E numbers are often grouped together without context.

In reality, whilst some E numbers are a signpost for where a product might be deficient in any whole food ingredient, they are not always a warning system or a measure of how “good” or “bad” a food is.

Essentially, the E number system is a regulatory classification system used across Europe to identify food additives that have been formally assessed and approved for use. The presence of an E number does not indicate whether an ingredient is natural or synthetic, highly processed or minimally processed, beneficial or harmful. It shows that the ingredient has been evaluated and assigned a standard reference number.

Much of the confusion comes from how abstract E numbers appear compared to familiar ingredient names. A number can feel more intimidating than a word, even when both refer to the same substance. As a result, E numbers are often misunderstood as markers of risk rather than tools for transparency.

This article is not about telling you which ingredients to avoid. Instead, it explains what E numbers are, why they exist, and how they are used, so they can be understood in context rather than feared on sight.

What Are E Numbers?

E numbers are codes used in the EU and UK to identify food additives that have been approved for use in food. The “E” simply stands for Europe, and the system was created to make ingredient labelling consistent and clear across different countries and languages.

Before an ingredient is given an E number, it must undergo a safety assessment and formal authorisation. This process evaluates how the substance is used, how much people might consume, and whether it is safe at those levels. Only once it meets these criteria can it be legally added to food and listed with an E number on packaging.

It’s important to understand what E numbers do and do not represent. An E number does not tell you whether an ingredient is natural or synthetic, and it is not a warning label. It is simply a regulatory identifier. In fact, many familiar and naturally derived ingredients, such as citric acid or lecithin, also carry E numbers.

Outside the EU, the same additives are often used without the “E” prefix, even though the substance itself is identical. The E number system is therefore best seen as an administrative tool for standardised labelling, rather than a judgement on the quality or safety of an ingredient.

What Is a Food Additive?

At its simplest, a food additive is an ingredient added to a food to perform a specific technical function. That function is not about marketing or nutrition, but about making food safe, stable, consistent, and usable at scale.

Common reasons additives are used include:

- Preserving freshness and extending shelf life

- Preventing oxidation, discolouration, or spoilage

- Stabilising texture and preventing separation

- Controlling acidity or pH

- Enabling emulsification, so oil and water remain evenly mixed

Including examples helps demystify this. Without additives, many everyday foods would separate, spoil quickly, or behave unpredictably during processing and storage.

A key point often missed is that additives are classified by what they do, not where they come from or how “natural” they sound. An additive can be plant-derived, mineral-based, or produced through fermentation, yet still be regulated under the same framework as a synthetic compound if it performs a similar function.

Most food additives are not added for nutritional value. Instead, they support food safety, product consistency, and manufacturing reliability; all of which are essential in modern food systems.

How the E Number System Works

The E number system is designed to categorise food additives by what they do, not by how they are made or where they come from. Each approved additive is assigned a number within a defined range that reflects its primary technological function in food.

At a high level, the system is grouped as follows:

- E100–E199: Colours

Used to restore or maintain appearance that may be lost during processing or storage. - E200–E299: Preservatives

Help prevent spoilage caused by bacteria, moulds, and yeasts, extending shelf life and improving food safety. - E300–E399: Antioxidants and acidity regulators

Protect foods from oxidation, control pH, and help maintain flavour and stability. - E400–E499: Emulsifiers, stabilisers, thickeners, and gelling agents

Support texture, consistency, and stability, especially in products containing both fat and water. - E500 and above: Miscellaneous additives

Includes raising agents, anti-caking agents, gases, and some sweeteners, each serving a specific functional role.

It is important to note that while providing a comparable function, two ingredients in the same range may behave very differently in application and may come from entirely different sources.

Are All E Numbers Synthetic?

One of the most common misconceptions about E numbers is that they are all artificial or synthetic. In reality, this isn’t the case.

Many ingredients with E numbers occur naturally in foods or are chemically identical to compounds already found in nature or in the human body. Some are extracted directly from plants, others are produced through fermentation, and some are manufactured synthetically.

For example, several acids, antioxidants, and emulsifiers exist naturally in fruits, vegetables, or animal products but still carry an E number once approved for use as a food additive. Vitamins such as ascorbic acid (vitamin C) also have E numbers when used for their technological function rather than their nutritional role.

The key distinction is that “natural versus synthetic” describes how an ingredient is produced, not whether it is safe for consumption. All E numbers, regardless of origin, must pass the same safety assessments before they are approved for use in food.

Another reason E numbers cause concern is that they often hide ingredients people already recognise. In reality, many everyday, widely accepted food ingredients are assigned E numbers simply for regulatory consistency.

For example, vitamin C is listed as E300, vitamin E as E306–E309, and riboflavin (vitamin B2) as E101. Citric acid, naturally found in citrus fruits, carries the number E330, while lecithin, a plant-derived emulsifier commonly sourced from soy, rapeseed or sunflower, is E322.

Even oxygen has an E number (E948) when used in food packaging.

E Numbers and Ultra-Processed Foods

One must also rcognise the nuance around E numbers and ultra-processed foods (UPFs). An E number on its own should not be treated as a warning sign that a product is unhealthy or over-processed. Many essential, well-understood ingredients play legitimate roles in food safety and stability. However, the pattern of use matters. In heavily ultra-processed foods, large numbers of additives such as sweeteners, colours, flavourings, emulsifiers, and preservatives are often used together to compensate for a lack of whole ingredients, restore lost texture or flavour, and stabilise products that have been extensively refined. In these cases, E numbers are not the problem themselves, but they can act as an indicator of how far removed a product is from its original raw materials. Context, formulation intent, and overall food quality are far more meaningful than the presence of an E number alone.

E Numbers and Food Safety

All approved E numbers have undergone formal safety assessment before being authorised for use in food. In the UK and EU, this evaluation is carried out by bodies such as the Food Standards Agency or the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), which reviews toxicological data, exposure levels, and long-term safety.

Each additive is approved with clear conditions of use. Some have maximum permitted levels, while others are allowed under a “quantum satis” principle, meaning only the amount necessary to achieve the intended technical effect may be used.

That said, a small number of people may be sensitive to certain additives, just as some individuals react to naturally occurring foods like nuts, lactose, or caffeine. However, true intolerance to food additives is relatively uncommon and typically depends on the specific ingredient, the dose consumed, and individual sensitivity.

Crucially, “approved” does not mean unlimited use, and the presence of an E number does not automatically indicate risk. Safety lies in regulation, responsible formulation, and appropriate consumption levels, not in the label code itself.

E Numbers vs Clean Label

E numbers and clean label are often treated as opposites, but in practice they are not the same thing at all. Clean label is a marketing and consumer perception concept, while E numbers are part of a regulatory classification system. One does not cancel out the other.

An ingredient can be naturally derived, widely used, and considered clean-label friendly, yet still carry an E number under EU and UK legislation. Lecithin is a good example. It is plant-based, familiar, and functionally essential in many foods, but is legally designated as E322. The E number does not make it less natural or less safe, it simply reflects how it is regulated.

The disconnect often arises because consumers associate E numbers with artificial or heavily processed additives, even though this is not what the system was designed to communicate. Regulatory approval focuses on safety, function, and permitted use levels, while clean label focuses on transparency, recognisable ingredients, and trust.

In reality, clean label formulation is less about removing E numbers entirely and more about making informed, justified ingredient choices. Clear labelling, honest communication, and thoughtful formulation matter far more than whether an ingredient appears as a name or a number.

Key takeaway: clean label is about trust and transparency, not the automatic absence of E numbers.

Common Myths About E Numbers

E numbers are often surrounded by assumptions that don’t stand up to scrutiny. Below are some of the most common myths, and what actually sits behind them.

“All E numbers are artificial”

❌ False. Many E numbers refer to substances found naturally in foods, such as vitamins, minerals, acids, and plant-derived compounds. The E number reflects approval status, not origin.

“E numbers mean a food is ultra-processed”

❌ False. E numbers appear in a wide range of foods, including everyday staples. Their presence alone does not define how processed a product is.

“No E numbers means additive-free”

❌ Misleading. Some ingredients perform additive functions but are declared by name rather than by E number, depending on formulation and labelling choices.

“Natural ingredients don’t have E numbers”

❌ False. Many natural substances, including vitamin C, lecithin, and citric acid, have E numbers because they are regulated additives.

How to Read an Ingredient List More Intelligently

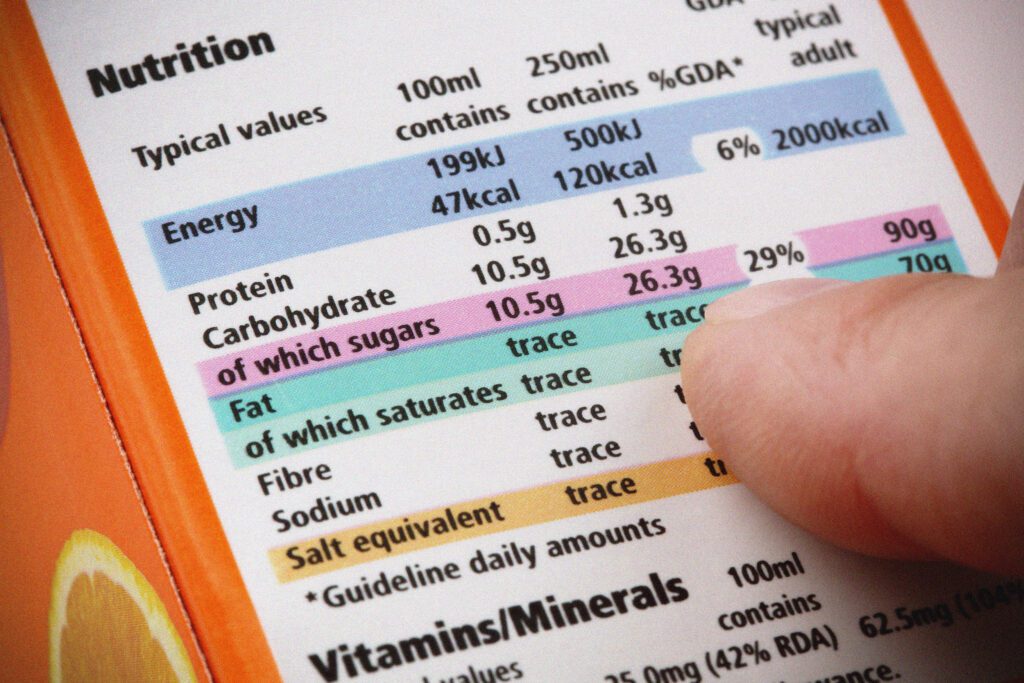

Ingredient lists are often treated as a shortcut to judging food quality, but they work best when read with context rather than fear. Instead of focusing solely on whether an ingredient has an E number or a technical name, it’s more useful to understand what that ingredient is doing in the product.

Ask practical questions: Is it preserving freshness? Preventing separation? Improving texture or stability? Many ingredients exist to solve specific, unavoidable problems in food production. Removing one component rarely eliminates the need for that function, it usually means it’s achieved in a different way.

It’s also important to consider quantity and context. An ingredient used at a fraction of a percent to stabilise a sauce or prevent spoilage plays a very different role to a primary ingredient. Functionality doesn’t disappear simply because an ingredient is removed or renamed; it is replaced, reformulated, or achieved through another system.

Request a Sample

Frequently Asked Questions: E Numbers

E numbers are codes used in the UK and EU to identify approved food additives. They exist to make ingredient labelling consistent across languages and countries. Each E number represents an ingredient that has been assessed for safety and authorised for specific uses in food, such as preservation, emulsification, colour stability, or acidity control.

No – E numbers are not inherently bad. An E number simply means an ingredient has been evaluated and approved for use. Some E numbers appear in ultra-processed foods, which contributes to their negative reputation, but the E number itself is not a measure of healthiness or risk.

Yes. The UK continues to use the E number system following Brexit. While a small number of additives have been restricted or removed based on updated safety data, most E numbers remain approved and regulated under UK food law.

Approved E numbers are not considered carcinogenic at permitted usage levels. All authorised additives undergo toxicological assessment before approval. Some ingredients have been restricted or banned in the past when new evidence emerged, which shows the system is actively monitored and updated.

No. Many E numbers are:

Naturally occurring compounds

-Extracted from plants

-Produced by fermentation

-Identical to substances found in the human body

For example, vitamin C (E300), lecithin (E322), and citric acid (E330) all carry E numbers.

“No E numbers” is a marketing or clean-label claim, not a regulatory one. The same ingredients may still be present under their full names instead of their E numbers. Removing the code doesn’t remove the functionality, it just changes how the ingredient is declared.

There is no direct evidence that E numbers as a group cause weight gain or inflammation. Health outcomes depend on:

Overall diet quality

-Energy intake

-Individual sensitivity

-Specific ingredients and doses

Associations often relate to dietary patterns, not the presence of E numbers alone.

Most people tolerate food additives well. A small percentage of individuals may be sensitive to specific additives (such as certain colours or sulphites). This is ingredient-specific, not E number wide, and is typically managed by reading labels carefully rather than avoiding all E numbers.

The number range indicates function, not risk:

E100–E199: Colours

E200–E299: Preservatives

E300–E399: Antioxidants & acidity regulators

E400–E499: Emulsifiers, stabilisers, thickeners

E500+: Miscellaneous (raising agents, gases, sweeteners)

The same additives are often used globally, but the “E” prefix is specific to Europe. In other regions, the ingredient may appear under its chemical or common name without an E number, even though it is functionally identical.

No. Foods without E numbers can still contain:

-Preservatives

-Emulsifiers

-Stabilising systems

-Processing aids

Removing one additive usually requires another functional solution, the chemistry doesn’t disappear.

That’s a personal choice, but understanding context matters more than avoiding numbers. Another approach is to consider:

-What the ingredient does

-Why it’s there

-How much is used

-The overall nutritional profile of the food

Some artificial food colours (such as certain E100 series colours) have been linked to behavioural effects like hyperactivity in children, particularly those who are sensitive. This led to voluntary reformulation and warning labels in the UK and EU. However, these effects are not universal, and naturally derived colours can also carry E numbers. The key issue is overall dietary pattern, not occasional exposure.

Aspartame is one of the most extensively studied food additives in the world. Regulatory authorities, including EFSA and the FDA, consider it safe within established acceptable daily intake levels. Ongoing debate reflects differences between hazard classification and real-world risk, not evidence of harm at normal consumption levels. For most people, exposure remains well below safety thresholds.

Sodium nitrite is used to prevent harmful bacterial growth and protect food safety in cured meats. At high intakes, and particularly when combined with frequent consumption of heavily processed meats, it has been associated with increased health risk. However, its use is strictly regulated, and risk relates to frequency, quantity, and overall diet, not the presence of E250 alone. Moderation remains the key factor.